Andrew Rae, Professor of Engineering, University of the Highlands and Islands

The Sustainable Aviation Test Environment (SATE) project was initially predicated on evaluating existing and emerging technologies against real-world use cases. Over time, it has extended into an understanding of how the new and different operational and economic possibilities these technologies provide can enhance the resilience of communities and businesses in previously under-serviced regions. Using the existing air services which have served these communities well for decades as a benchmark, SATE has looked at alternatives for the transport of both passengers and freight as well as new markets that require different vehicles and different operational capabilities.

Early island services

The impact of these services extends back to the instigation of air services in the islands in the 1930s. My colleague Professor Donna Heddle examined these effects and concluded that the greatest impact was not due to the connectivity to the Scottish mainland, but due to the connection of the outer islands with Orkney mainland.[1] This was particularly noticeable in infant mortality rates which improved dramatically because the air ambulance service could connect the outer islands with the hospital in Kirkwall in a matter of minutes, whereas the ferry could take a couple of hours, if it was running. Perhaps counterintuitively, the air services were often able to run in periods of bad weather when the ferries could not; a short weather window (a drop in the wind or a break in the clouds) allowed the aircraft to fly when the sea-state did not abate sufficiently to permit a boat to leave harbour.

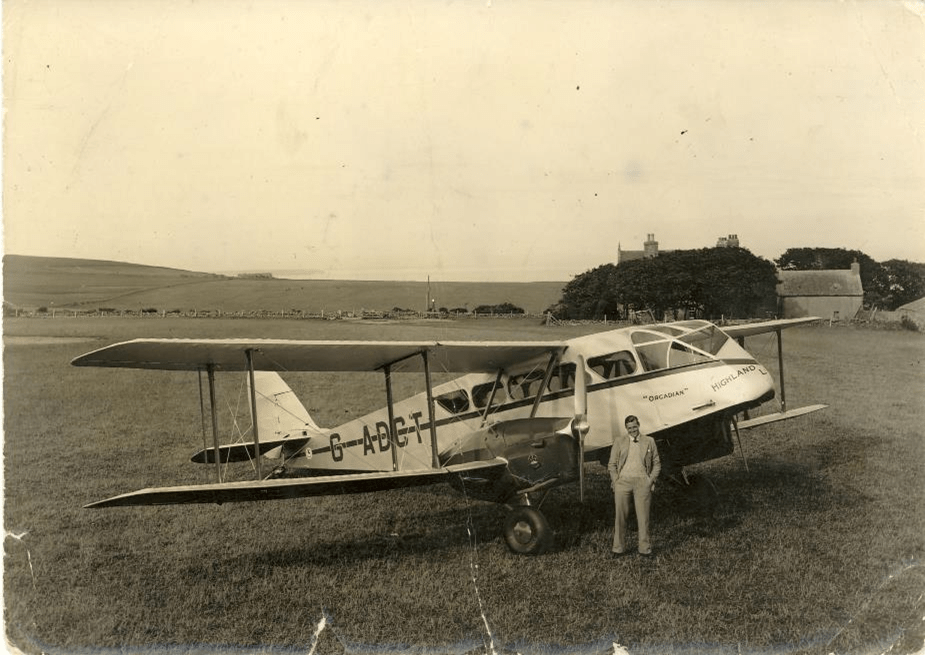

Given that my grandfather was one of the pilots flying these services in the 1930s, I hope you’ll indulge me in looking briefly at the changes in air services in the 90 years since the days when wood and canvas biplanes such as the wonderful de Havilland Dragon plied these routes. A London to Orkney journey by air in the 1930s took six hours which, if one adds time for check-in, security and baggage collection, is not much different than that available now. This is perhaps surprising given that the cruising speed of the current aeroplane on the Edinburgh/Glasgow to London sector is about four times faster than the de Havilland Dragon used in the 1930s!

The next generation of aviation

So, connectivity between the main hubs has hardly changed, neither has the difficulty of getting to the littoral towns in the Highlands of mainland Scotland. Road journeys of up to six hours or a train journey of up to seven hours, are necessary to reach Ullapool or Thurso, whereas a flight from Edinburgh or Glasgow to Stornoway or Kirkwall takes about an hour. Thus, while the transport of people, mail, newspapers and smaller items of freight to and from the main island airports has become commonplace, the same activities around the Highlands or to the outer islands remain the domain of road, rail and shipping routes. It is these historically more-isolated communities and businesses that will benefit most from the work being done in SATE.

A brighter future with SATE

Perhaps the pioneers like John Sword (who founded Midland & Scottish Air Ferries), Ted Fresson (Highland Airways) and Eric Gandar Dower (Aberdeen Airways) would approve of the work now being conducted where once they toiled, as we endeavour to forge new routes, new operations, and new opportunities for the benefit of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Bringing different aircraft that use green energy will help deliver the goal of net-zero aviation in the region. Increasing connectivity while simultaneously reducing environmental impact is an objective worth chasing. And if it can work here, it can work anywhere.

You can find out more about Andrew and his work here.